The world has woken up to the discernible cost of burning fossils and the reality of climate change. Yet the larger socio-ecological injustice perpetuated by the fossil industry in the form of infringement of rights of local communities, destruction of natural ecosystems, and exploitation of labour has not rattled our national and global institutions or found mainstream acknowledgment in global political discourse.

The extractive psychology of the fossil industry is entrenched with malpractices and disregard for social and environmental concerns. It has been estimated by the IPCC in 2018 that fossil fuels alone were responsible for 89% of the global CO2 emissions in the world and constituted a major part of the 1C increase in the global temperature. Around 100 million hectares of the Amazon Rainforest have now been occupied for exploration and drilling of oil and gas. India has officially reported 76 major fly ash breach incidents from thermal power plants in which human lives were lost, nearby water sources were polluted, and damage was caused to the flora and fauna of the plant. The history of the fossil industry is marred by practices leading to rampant environmental destruction and violation of the rights of local communities across the globe.

As we transition to clean energy, the voice for ‘just transition’ is growing louder. Just Transition means that the phasing out or phasing down of coal and the corresponding increase in renewable should be fair and just for the stakeholders of the transition. It implies that the renewable energy sector should not repeat what the fossil fuel industry was doing and ensure that the coal sector workers being laid off are rehabilitated, the rights of nature are protected, and the communities’ resources are not exploited. In the following sections, we will see what the energy transition is looking like in practice and how ‘just’ it really is.

Energy Transition: A New Paradigm or Perpetuation of an Old One?

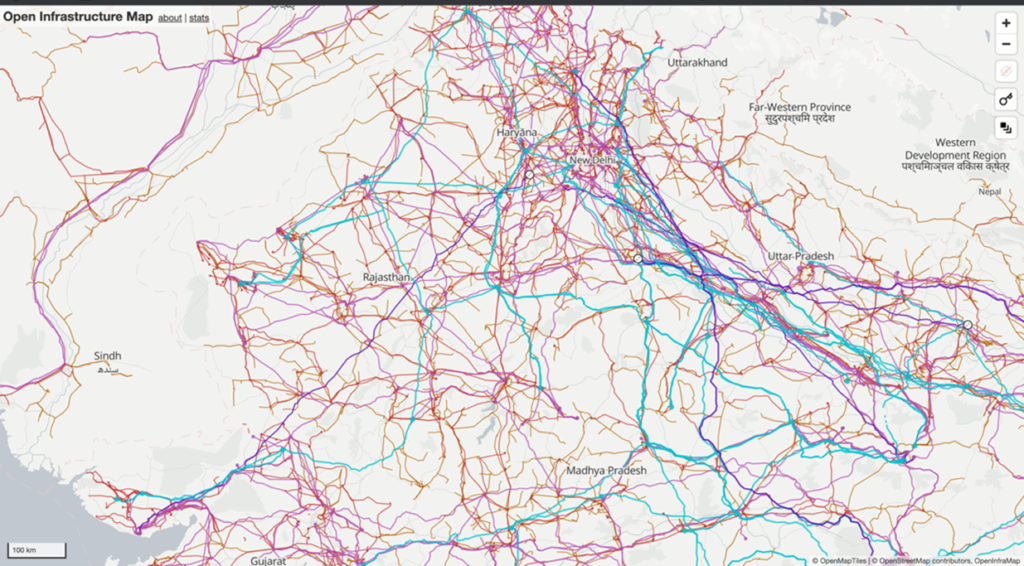

Following the Supreme Court of India’s order directing the constitution of a committee to protect the critically endangered species from the high voltage transmission lines being laid down as a part of solar projects in Rajasthan , a news article with the headline ‘A giant, poor-sighted bird stands in the way of India’s green energy goals’ was released. The article was meant to compare the costs and benefits of energy transition specific to the commissioning of new solar transmission projects in the habitat of the Great Indian Bustard (GIB).

GIB, an endangered avian species native to Western Rajasthan, Kutch, and some parts of Pakistan, is a majestic bird known for its striking appearance, with a tall and slender body, long legs, and a distinctive black crest on its head. It has a remarkable ability to fly long distances, despite being one of the heaviest birds on the planet. However, only 150 GIBs are left in the world as the rest have become a victim of increasing human activity in their habitats.

The notion painted in the aforementioned article trivialises the ‘rights of nature’, callously undermining the death of the birds as a result of the dense transmission network violating their natural habitat.

Figure 1: A Great Indian Bustard that allegedly died due to a collision with power lines. (Source: Mongabay India)

Figure 2: Map of transmission lines in India (Source: Open Infrastructure Map)Rights of Nature

Aldo Leopold , an American Philosopher and Conservationist, propounded the theory of ‘land ethic’ where he expanded the definition of ‘community’ to include all aspects of nature and argued for an equal position (or rights?) to that of human beings. The theory perceived nature with the same love and respect we attribute to members of our community. This was also theorised by Arne Naess, a Norwegian Philosopher, through his Deep Ecology Theory. This theory advocates that the extent of protecting nature should not be restricted to what we need for our survival. It should, instead, be deep and comprehensive and inclusive of all aspects of nature, irrespective of whether humans are getting any benefit from it or not. Vandana Shiva, an Indian Academician and Ecofeminist, addresses our planet as Mother Earth and passionately argues for the protection of the inherent rights of Mother Earth. She supports the personification of nature as a living system and advocates the need to foster respect and cooperation with nature.

A similar set of values is observed amongst many communities in India since ancient times. For instance, the Bishnoi community of Rajasthan considers nature sacred, and many people of the sect have sacrificed their lives to protect and preserve the environment. The Dongria Kondhs of the hilly regions in Odisha worship the hills in their villages as a deity known to them as Niyam Raja, and this right to worship was recognised by the Supreme Court in 2013 when Vedanta wanted to mine the said sacred hills.

In more contemporary times, in the case of T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad vs. Union of India & Ors. , the Indian Supreme Court observed that – “Environmental justice could be achieved only if we drift away from the principle of anthropocentric to eco-centric.” Thus, the idea to protect and preserve nature not just for our sake but also for every single aspect of nature is not foreign to our way of thinking and has been prevalent in human civilization for a long time.

The Clean Energy Transition

India, in its Nationally Determined Contributions, has committed to net zero emissions by 2070 which shall require, amongst other things, large-scale deployment of renewable energy and decommissioning of fossil fuel-fired power generation. However, clean energy is likely to have many unintended consequences. The complexities of the clean energy transition are discussed herein under:

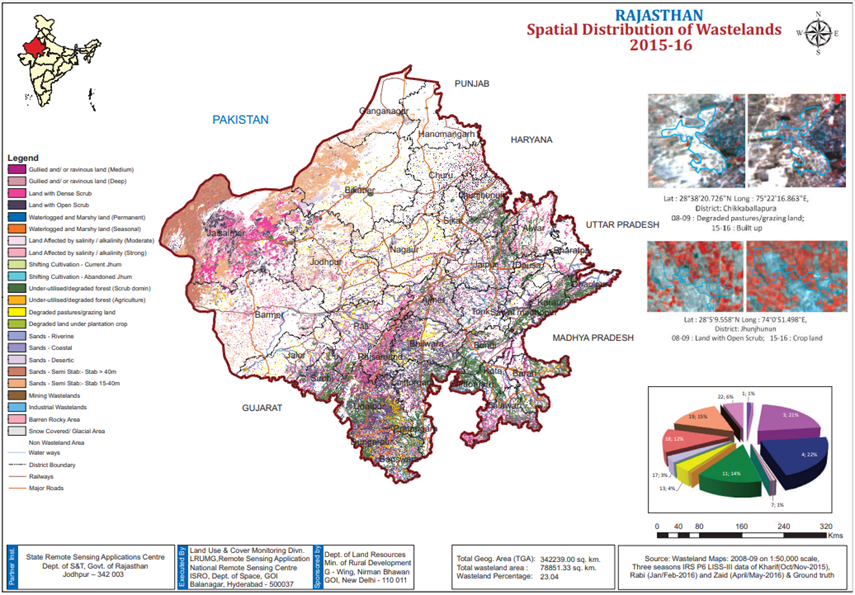

It has been estimated that 50,000 sq. km of land shall be taken up by solar power plants in India by 2050. It is interesting to note that certain other estimates such as Van der Ven et al and Gulagi et al that indicate a lower requirement for land, do not include desert and scrubland in their study. Such land has been termed as ‘zero impact areas’ or ‘wasteland’ based on the reasoning that these lands do not have any commercial or agrarian value. This colonial practice in the classification of land is at the centre of social-environmental injustice perpetuated in the name of the clean energy transition.

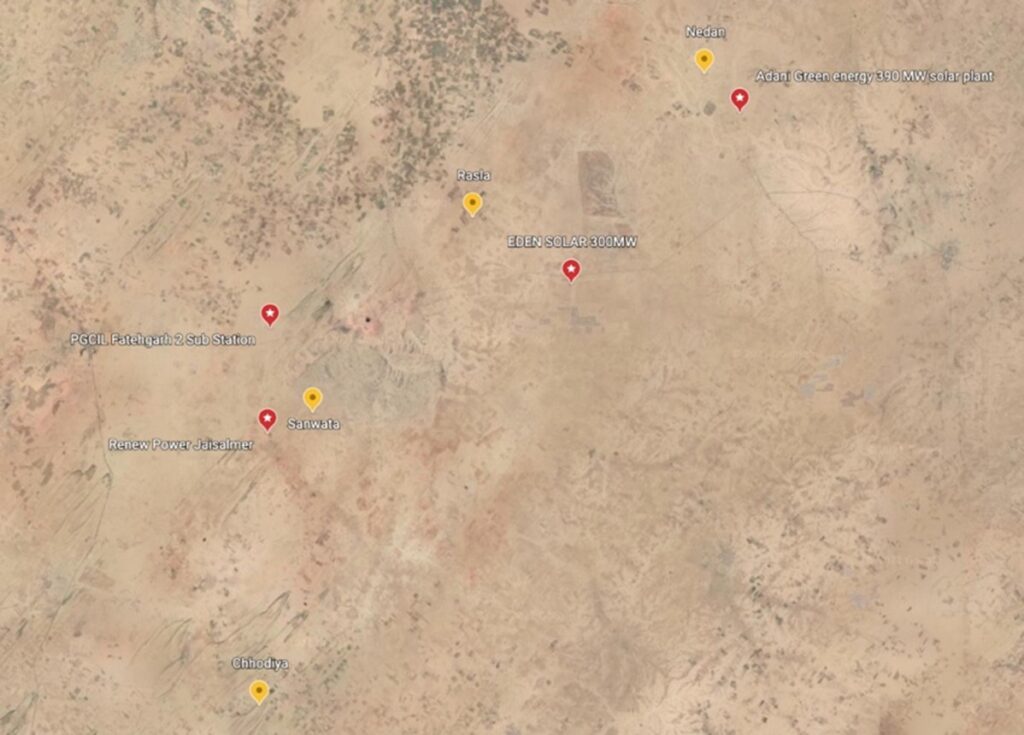

Deserts and scrublands are home to ‘unique ecosystems’ and biodiversity. They include pastoral lands, agricultural lands, and Orans (sacred forests). For instance, the Oran (sacred grove) near the Sanwta Village might seem like a barren land from a satellite view, but on the contrary, it contains a diverse ecosystem that includes the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard and the Lesser Florican.

The perception of these areas in Rajasthan as wastelands leads to a narrative that involves plans for their conversion to ‘productive lands’. Currently, these wastelands have been identified as hotspots for commissioning solar power plants. The Bhadla Solar Park uses 14,000 acres of desert land that belonged to the State, but the land has been historically used by locals for grazing. After the installation of solar panels on this land, all domesticated animals in the area have lost their source of food.

During the commissioning of solar parks in Jodhpur, a large number of Khejri trees were felled. This move was highly opposed by the Bishnoi community which considers trees to be sacred. The tree is also an essential part of the desert ecosystem as it can survive dry weather, provides fodder and wood, and helps maintain the soil’s nutrient value. Thus, the rapid commissioning of solar power plants in the ‘wastelands’ of Rajasthan as a part of the energy transition in India has certain pitfalls that are directly impacting the unacknowledged ecology of these areas.

Conclusion

The various examples discussed in this article suggest that India’s clean energy transition seems to carry the values of the fossil industry which placed development over the rights of people and the environment, perpetuating injustice in various forms. This isn’t surprising as a clean(er) technology does not necessarily foster an ecology-centric consciousness. The development paradigm from the fossil era that favours centralised, large-scale energy infrastructure and undermines the rights of local communities as well as that of nature is seemingly shaping India’s clean energy transition also. This is perpetuated by the institutions and consciousness of the colonial past, as well as the State directed model of development.

Currently, Rajasthan has an installed solar capacity of 16 GW and this capacity has been slated to be increased to over 60 GW by the end of this decade. This rapid ramping up of solar without a wholistic approach has the risk of increasing the severity of the aforementioned pitfalls of the energy transition.

Delivering justice in the course of clean energy transition shall require a transformative change in our existing institutions and economic systems. This is unlikely and difficult unless our larger social consciousness evolves to recognise nature as a living system. Until such time, recognising and institutionalising ‘rights of nature’ may serve as a critical instrument to mitigate the environmental impact of an unchecked transition.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/14/climate-global-fossil-fuel-use-accelerating-and-set-to-get-even-worse.html

- https://news.mongabay.com/2013/05/is-it-possible-to-reduce-the-impact-of-oil-drilling-in-the-amazon-rainforest/

- https://carboncopy.info/wp-content/uploads/FLY-ASH-REPORT-FINAL_JULY-23.pdf

- https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/what-just-transition-and-why-it-important

- https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2019/20754/20754_2019_31_1502_27629_Judgement_19-Apr-2021.pdf

- [1] https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/science/a-giant-poor-sighted-bird-stands-in-the-way-of-indias-green-goals/article34818175.ece#:~:text=Pity%20the%20great%20Indian%20 bustard,grasslands%20of%20India’s%20western%20borders

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/gallery/wildlife-and-biodiversity/great-indian-bustard-in-pics-mighty-but-critically-endangered-87079

- https://www.aldoleopold.org/about/the-land-ethic/

- https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/5186/3390

- https://www.garn.org/vandana-shiva-president-tribunal/

- https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/bishnoi-villagers-sacrifice-lives-save-trees-1730

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/vedanta-have-faith-tribal-belief-is-ecological-40885

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/187366700/

- https://unfccc.int/NDCREG

- https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Renewable-Energy-and-Land-Use-in-India-by-Mid-Century_September-2021.pdf

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-82042-5

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0180611

- ibid

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/wasteland-conversion-threatens-livelihoods-ecological-balance/article29994100.ece

- https://www.bbc.com/news/business-62848096

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/states/villagers-stir-against-solar-plants-protects-khejri-trees/article65625082.ece

- https://npp.gov.in/dashBoard/cp-map-dashboard

- https://cea.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/notification/2022/12/CEA_Tx_Plan_for_500GW_Non_fossil_capacity_by_2030.pdf